That, fair reader, is Bologna. Well, it's Bologna from a speeding train, heading from Rome to Venice. I have yet to to have the pleasure of a proper visit. But when I do finally place my feet on terra firma in the capital of Emilia-Romagna, there are four things that I have to go for. The first is balsamic vinegar. Second, prosciutto di parma. Third, Parmesan cheese. And the fourth, of course, is the dish which gets its name from this city, Bolognese.

Now, you may think you know all about Bolognese. You can head to "Neighborhood Fast Casual Italian Place" and get "Bolognese" ladled on to which ever endless bowl of noodles you choose for that service. In the UK, you can get spag bol in pubs, or at the local supermarket, pre-fab. Wherever you get it, it's a tomato-based sauce, studded with little balls of ground beef. It really seems that the world outside of Bologna is intent on creating the following logic:

Marinara + ground beef = Bolognese. QED.

Except that red gravy is not Bolognese. I'm sure, you're saying, "Who the hell are you to definitely claim what Bolognese is? I like the Tour of Italy!!" Cool your jets. I'm just the messenger for the Accademia Italiana della Cucina. In 1982, they submitted an official definition to the Bologna Chamber of Commerce. And marinara + ground beef sure as hell ain't it.

You want the truth? You can't handle the truth! I mean, I hope you can because otherwise you won't be able to handle making real Bolognese. Whereas "meat sauce," as I will call most American and British renditions, is a quick, loose, tomatoey affair, Bolognese is a thick, rich, meaty, dairy-based, paste.

For that reason, Bolognese is less of a sugo--the word which means what we normally think of 'sauce'--and more of a ragù. So what makes a ragù? Meats braised in wine and broth were a common-place in Italy for centuries. But it seems that they were rarely served on top of pasta, but rather as a protein eaten as a main dish after eating the broth with noodles or bread like soup.

Enter Napoleon, France's favorite Italian. In 1796, Napoleon invaded Italy on behalf of Revolutionary France. With his troops, he brought ragôut. And apparently the fashion caught on. The first appearance of "ragù" in an Italian cookbook dates precisely from this period of Napoleonic occupation, from a town near Bologna named Imola. Over the course of the 19th century, the use of such meat-based sauces grew in popularity, particularly among wealthy Italians. And in 1891, in a famous Italian cookbook entitled La scienza in cucina e l'arte di magiar bene (The Craft of Cooking and the Art of Good Eating), Pellegrino Artusi crafted a text attributed with creating a national, Italian culinary culture.

And guess what? Bolognese was in Artusi's book.

Now, let's take a closer look at the Accademia's recipe. For those who don't speak Italian, here are the basic inputs: coarse ground beef, pancetta, carrot, celery, onion, tomatoes, milk, white wine, broth, and the alluring panna di cotura (more on that later).

It's not gonna be quick or easy. But damn, is it worth it. Over hours of slow bubbling on the stove, it's the magical path to concentrated bovine goodness.

Bolognese is really all about the cow, in all its lo-ing majesty. It uses each product thoughtfully and strategically. The "very little tomato" part may make sense to you by this point. Tomatoes weren't necessarily the be-all end-all in Northern Italy in the late 18th-century, when the concept of ragù first appeared. And what about that dairy? Well, Emilia-Romagna is known for excellent bovine products. They use so much dairy for their cheese industry that they require milk deliveries from Lombardy, a contiguous province. And, hey, Parmigiano Reggiano is known as the King of Cheese. So, for business elites like Artusi, it would make perfect sense to spotlight the city's beef, dairy, and cheese at one shot. Kind of like Cheese Curds at the Wisconsin State Fair, the spotlights the best livestock and dairy the region could offer. It's Bologna in a bowl.

And culinarily, it doesn't hurt that simmering beef in dairy makes it soft, unctuous, and slightly sweet. What investor wouldn't want to help out the dairy industry of Emilia-Romagna after a bowl of this? That's great synergy, Artusi. On point.

So without further ado, let's celebrate the cow. Moo.

Ragù alla bolognese

1 tablespoon olive oil

3 tablespoons of butter

4 oz. pancetta

1 large carrot

2 stalks celery

1 large yellow (NOT SWEET) onion

1.5 pounds ground beef

14-oz can whole peeled tomatoes -or- one small can tomato paste

1/2 cup dry white wine

1 cup of whole milk

2 cups of chicken stock

1/2 cup of grated Parmesan cheese

One pound pappardelle, tagliatelle, or fettuccine

Pop that pancetta in a food processor and really blitz it.

Pancetta you've met before. But now, it's a supporting actor. Just blitz it up REALLY fine, and dump in your pan with a tablespoon of butter, to start rendering the fat. When there's a nice pool of fat in the pan, you're gonna plop your minced carrot, celery, and onion (note: no garlic!) into the fat.

Cook until the mirepoix is soft and fragrant and *slightly* browned, about 5 minutes. In the meantime, read about mirepoix. First, it's pronounced "MIR-pwa". Yes, that's French. If you're at all familiar with French cookery--or have every seen an episode of Julia Child--you'll know that virutally every dish uses these three ingredients to create the gustatory scaffold upon which flavors are subsequently built. Carrots are sweet; onions and celery are aromatic. Put them together, and you've got a very pleasant flavor profile. Just think of chicken soup. Exactly. And note that bolognese does not have any herbs or spices. This is it folks. The mirepoix is absolutely vital.

In general, the concept of mirepoix exists in a diverse range of world cuisines, but in different guises. In Italy, it is called "soffritto," for "under-fried." It seems that the content of soffritto is somewhat more vague than the certain, hard-core French cousin. But it strikes me that, given the Frenchified origins of ragù, the soffritto common to Bolognese can be understood as yet another borrowing from Italy's bellicose neighbor to the northwest.

Okay, it's probably under-fried by now. Pull it out and reserve it.

Now, drop about a tablespoon of olive oil and another tablespoon of butter into the pot. And now place about a third of your ground meat in the pot, set to high heat. You'd be well within your right to use a 50-50 blend of sirloin and chuck, which would grant you meatiness and moisture, respectively. But if you want to go for maximum bovine bliss on the dish, I recommend going for coarsely ground skirt steak. It has a lot of connective tissue, and an awesome, meaty flavor. Perfect for our long braising technique.

When at the supermarket, go up to the butcher, introduce yourself, and ask for skirt steak, coarsely ground. This is what life was like before the supermarket did all the meat stuff pre-fab. Get to know your butcher; get to know about different cuts of meat. That way, you can pull stuff like this and impress the hell out of everyone. Just be sure to thank your butcher afterwards, okay?

You're gonna want to cook the meat in about 2 or 3 batches because you want to get a good, dark crust on the meat. If you put all the meat in at once, all that water coming out of the meat will create a moist cooking environment. Not exactly conducive to a hard, dark sear that we want. Don't crowd the pan and no worries. Cook each batch until you hear the popping of grease, which means that all the water has been evacuated. As you work, consider this: if beef is predominantly protein and fat, how does it get "caramelized"??

Yeah, it's an excellent question. In fact, it would be largely incorrect to say that we caramelize meat when we sear it. In fact, the meat undergoes something called the "Maillard Reaction" when placed under hot, dry conditions, as currently prevail in our pan. Essentially, instead of sugars reforming and making weird compounds, slowly driving out water and adding carbon to the mix, ultimately turning caramel brown--or black, if you've ever screwed up a candy, it is amino acids that are in flux. The heat breaks and re-forms bonds between various parts of protein bands, making them bond with sugars in the meat, with each other. It's like Burning Man. As the heat goes up, stranger and stranger linkages happen. Until everything is golden-brown and...delicious? Guess the metaphor falls apart...maybe...

Check that meat.

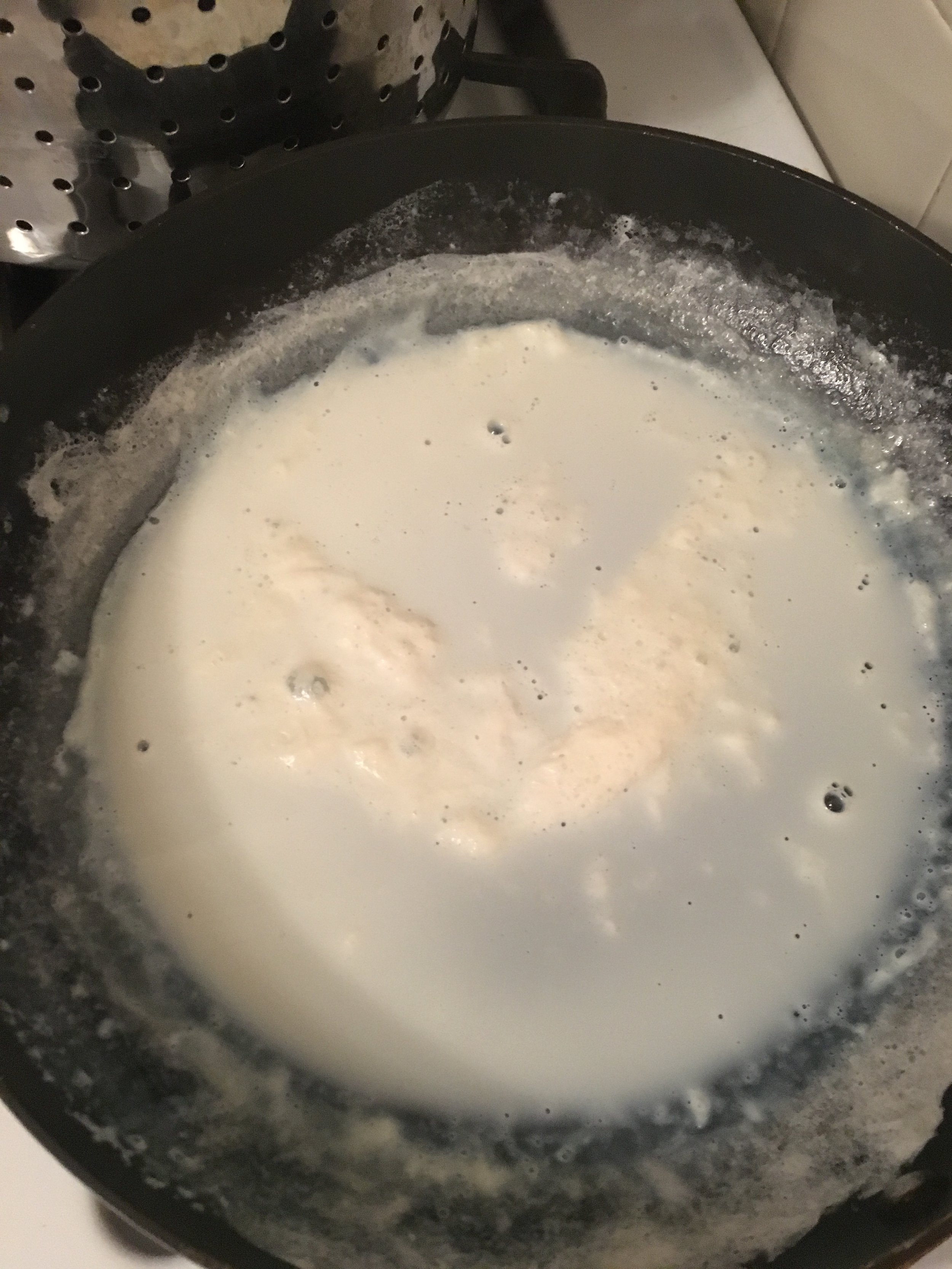

See brown bits on the bottom? That's just what we want--remember our vocab: sucs. We're gonna dissolve that rich fond in our next step. Put all the meat and our reserved mirepoix back into the back and pour the wine in. Scrape the bottom as best as possible to dislodge those good bits. When that reduces by about half, add one cup of the milk. It will look--somewhat unappealingly--like this:

Now, add your tomato accent. The dish calls for pasatta or whole peeled tomatoes, in keeping with the vibrant agricultural vibe of the dish. No bells and whistles here. In my version, I used some canned cherry tomatoes. I don't really advise using them, as they're a little sweeter than welcome and for some reason, still have a peel on them. But I would REALLY recommend using a can of tomato paste for your redness. Why? Well, paste is basically just that bottle of pasatta, after it's been cooked down until it's solid. And basically, we're trying to do just that with this sauce--driving water away to concentrate flavor. So why add more water that we're just going to evaporate out anyway? Exactly. Use paste!

Finally, if you happen to have a rind of Parmesan cheese lying around, because you've been such a dutiful follower of this blog, you don't have to throw it away. Tuck it lovingly into the sauce for chowing down on later. That's your fringe benefit as the chef du jour. AND it enhances the sauce, because it'll allow some of the delicious compounds to come into our matrix, kind of like bones in a broth. Win/Win.

Now, here's the time-consuming part. Mix 1/2 cup of milk with one cup of broth. You're gonna leave your ragù on low heat, just barely burbling. If things start looking dry, or every 30 minutes or so, add a half-cup of our broth-milk mix. Use one of the nicer, cartoned varieties of stock. You will be rewarded.

Why do you have to wait so long? I know it's hard, but its worth it ("He says that a lot"). Well, if you were to pull the sauce after 30 minutes, sure, it'd taste pretty good, but it would lack the beauty of a long simmered ragù for a couple reasons. Essentially, what we're making here is a stove-top, ground-beef-based pot roast. We're doing a braise. Normally, for a braise, you take a big hunk of fibrous meat and cook it in a moist environment for a couple hours. That transforms the fibrous rubber bands of connective tissue made of collagen into delicious and ooey-gooey gelatin. Grinding the meat just happens to increase the surface area-to-volume ratio, which, if you've every had dry pot roast, you know is very wise. Gain access to that collagen, bust it up, and get out as quickly as possible. Now, we can use a cut of meat that normally isn't ideal for braising (skirt steak), and make it as unctuous as the best pot roast or brisket you've ever had.

See, I told you this dish makes beef look really amazing. Well done, Romagna.

Okay, so for those keeping track at home: you're gonna do four applications of liquid and a total of two hours of simmering. It should look a little something like this:

See how it's thick and has kind of an oily sheen on top? That is PERFECT. Basically, what we're looking for is to drive off most of the water in the sauce, leaving primarily the fat-phase behind. And honestly, you can feel free to keep adding liquid and simmering if you're really a glutton for suffering, as it probably will enhance the ragù. It's just diminishing returns, you feel? If you're gonna go full-nonna on this, just create more of that broth/milk blend and follow the same dosage schedule until you're satisfied. But really don't go longer than four hours, I'd say.

As your Bolognese matures, bubbling slowly but surely on its way to perfection, we now deal with the panna di cottura. Remember when earlier, I asked you to use a total of two cups in the sauce? Well, you should have residual milk in your bottle. When there's 30 minutes left in your cook, dump the milk into a pan, drop one tablespoon of butter in, and put the heat on under it at about medium-low. Don't boil it and don't burn it. Stir it every so often. We're reducing it.

This is absolutely genius. Panna di cottura means something like "cream of the cooked variety." If you are a dairy farmer, you get a ton of raw milk from cows, which is obviously non-homogenized. Normally, to get cream, you allow raw milk to sit, and it will separate into distinct layers, due to density-differences caused by fat content. The least-dense stuff floats. That's cream.

But if you're clever, you can have your cake and eat it, too. Put all that raw milk in a big vat and cook it down, slowly but surely liberating water and concentrating the stuff. By the end, you should get something that's essentially cream-like, but that also contains the best of the milky stuff, too--protein and sugar. This is the logic behind clotted cream, for those that have had the pleasure.

Above, we discussed tomato paste and the logic behind using it instead of tomatoes. Why add water-content if you are ultimately hoping to drive water away? Same logic applies with our milk. We can add additional concentrated milky content--creaminess, sweetness, fat--without having to sit at the stove for 3 hours. If you're really committed and not concerned about dairy-borne pathogens, try to find raw milk. If you're less committed, try to find non-homogenized milk. If you're using normal whole milk, it'll be good, too, don't worry.

Man, how awesome is dairy? Here's our second dairy application, and it is absolutely genius.

Here's what our panna di cottura looks like after about 10 minutes.

And after 20:

Now, dump our ad hoc clotted cream into our tender beef mix.

And get ready for dairy hit number 3: the incomparable Parmesan cheese. You gotta find real Parm for this. Don't buy the green cylinder. Don't get anything pre-shredded. Get a hunk of Parmesan cheese and grate it down. After all, Parmesan is like the star of the Emilia-Romagna cheese scene. So why would you setting for anything less than perfect?

And in terms of the cook, Parmesan adds a critical hit of umami to the already-unctuous lip-smacking goodness of the beef and fat. Parmesan is so mouth-watering due to the presence of glutamates. Glutamates are amino acids which appear in fatty meats, mushrooms, and cured products, aged cheese included. In other words, the addition of Parmesan cheese will make the beef taste even beefier! This is another absolute stroke of genius, having one of your amazing products support and riff off the flavor of another. Elegant culinary design, really.

By this time, get ready for your pasta. Typically, ribbons are used for bolognese, as they allow a maximum surface area to get all covered in the dairy-meaty-fatty-cheesy goodness. You could use fettuccine, which you're probably familiar with. But I would shell out for some really nice tagliatelle or even pappardelle. Pappardelle is the widest of the ribbon-style pastas, not including lasagne, which would be comically-large, but really delicious (that's another show, kids). Hell, it's name even comes from the Italian word for gobble up, "pappare." You should just go ahead and use pappardelle. When it's done, drain it, and of course, save some of the cooking liquid. Ready for emulsion. Return the pound of pasta to the cooking pot, put the heat on medium-low, and add about a 1/4 cup of cooking water back, and then add ladle after ladle of the Bolognese in, tossing the ribbons as you go. Add a little more Parm and keep tossing until the noodles have acquired a rosy sheen. You don't want the noodles swimming in the sauce, you want a beautiful fusion. If you have some ragù left in the pot, do not stress. Either add some to the top of your pasta pile as you're eating, or freeze it for the next application. Slam the top of your pasta with even more Parmesan cheese and that's all she wrote.

I applaud you all for sticking with me through this long, detailed, cook. I think you will find that it is decidedly worth the inconvenience. And in particular, I hope you found it amazing how so many cow-products could come together in such impressive ways to spotlight one-another. Bolognese reveals the luxury and richness that one can extract from basic products with some scientific and culinary know-how. I mean, pork fat is always sexy, so the Roman sauces already have appeal. But this ragù--and canny businessmen in Emilia-Romagna--had to work hard for the money. More than the other recipes we've seen so far, Bolognese shows that we can actually make new flavors by understanding everything that one animal offers. We get five different products used in this dish from cows--milk, butter, clotted cream, Parmesan cheese, and beef. And that, my friends, speaks to a very special relationship--and a very special wealth--that we can get from our bovine friends, even if it isn't immediately obvious from a cursory look at a barnyard speeding by our window.